A recent budget fight in the U.S. ignited an age-old discussion: Are the wealthy a threat to Democracy? In the last few years, Elon Musk, presently the wealthiest individual on the planet, (1) purchased Twitter (now ‘X’), a large social media company, (2) funded, in large part, a Political Action Committee to help elect Donald Trump, and (3) is now, seemingly, a direct power-player in American politics, peddling his money-backed influence to alter U.S. policy. Musk has gone so far as to threaten funding election challenges to any politicians who do not follow his agenda.

This has understandably worried many elected officials and members of the public. After all, ideally, no individual has more influence on our political process than anyone else, but that isn’t the system we live in.

How we got here

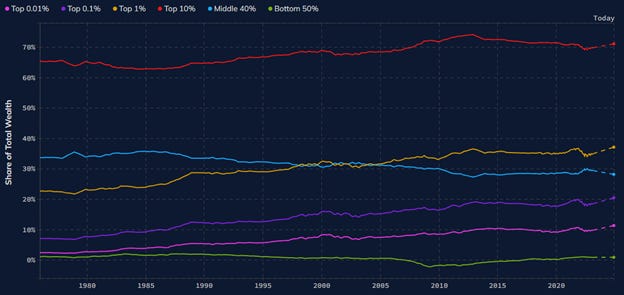

In a society dominated by private ownership, wealth inequality is essentially inevitable. However, wealth inequality increased substantially over the last several decades. The bottom 50% continue to own almost nothing as a percentage of total wealth, but the wealthiest have increased their total share substantially. The share of wealth owned by the top 0.1% nearly tripped, and the share owned by the top 0.01% nearly quintupled.

Wealth and income represent much more than descriptive levels of capital accumulation and purchasing power. They, in our market-oriented, mostly capitalist system, represent an individual’s freedom and relative power in society. Freedom to do something, in its most basic sense, is only accessible to an individual who has a meaningful, ever-present, ability to do said thing. In our system, the ever-present ability to do something is gate-kept and rationed, typically speaking, through markets and money. Want to enjoy a film with your friends? You’ll need an enterprise which allows you/your friends in, and you/your friends will also need enough money to pay for the ability to watch the film.

However, if you happen to not have an available movie theater, one that accepts you/your friends, one that offers the film you’d like to see, and one that offers a price you/your friends can afford, you, barring illegal means, are not meaningfully free to see the movie you want. There are many practical reasons why society couldn’t naively mandate all movies be free, but lack of freedom to enjoy the plenty around them plagues people in most aspects of every society, including the freedom to enjoy things we might consider rather necessary for survival: healthcare, housing, food, clothing, etc.

The freedom to enjoy proper access to basic needs is already a vulnerability in our economic system, but the relationship between money and power is perhaps a more salient example of the insidious nature of our economic organization and its necessary impact on our politics: people with more money have more political influence, and people with substantially more money have substantially more political influence.

In American, money in politics is exploding because the American system allows for relatively extreme levels of money in politics. Private donations, political action committees, lobbying, and wall to wall advertising capacity (among other things) combine for a highly unequal distribution of influence in politics. There’s a reason politicians must spend so much time on the phone and at events mingling with the wealthy. Candidates need money to run campaigns, and the wealthy have a disproportionately large amount of money, so baked into American democracy is the disproportionate influence of the wealthy in our politics.

Even progressive candidates who shy away from corporate and PAC contributions and openly criticize the role of money in politics are not immune to this. Progressive candidates who run for office still need to organize fundraisers and mingle with wealthy individuals to effectively raise money. Progressive candidates might advertise: “Our average contribution is only $32.50. This is a people-powered campaign!” There is some truth to this. Obviously, a person who only takes individual contributions and declines corporate/PAC contributions will likely have a wider, more horizontally distributed, base of donors, but this only goes so far, as the average person who contributes to a political campaign is wealthier, and wealthier people are more likely to donate towards the maximum legal limit(s).

Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (AOC) ran for re-election in 2024 and, as is typical, she only accepted individual contributions. She received over $4 million in individual itemized contributions in 2024. Below is a graph I put together with data from the Federal Election Commission.

This shows the top 1% of donors donated 11.2% of total aggregate individual itemized contributions. The top 20% donated a majority of total individual itemized contributions. This could, in some part, imply a very passionate minority of people who give every last dollar they earn to AOC’s re-election campaign, but more than likely this represents a highly skewed distribution of people who tend to be wealthier/higher income.

It's important to note that wealthy people don’t have a stubborn class solidarity on any particular issue. Higher income people, in aggregate, were 50/50 in their support for Kamala Harris and Donald Trump in 2024, with higher income people leaning towards Kamala Harris. This is despite Kamala’s policy of raising taxes on higher income people to pay for various social programs. We can also point to many assorted examples of policies being enacted despite oppositional attitudes from the wealthy, even in America: Social Security, Medicare, Progressive Taxation, Minimum Wage, etc. These policies lead to disproportionate burdens on the wealthy, and yet they were passed anyway. The wealthy’s disproportionate influence on politics only goes so far, but it does count, and it does influence the governance of our politicians, and assuming we believe that all people should have an equal influence on politics, this is a problem worth considering.

What to do

There are two main ways to restrict the wealthy from influencing our politics in a disproportionate manner: (1) Reduce wealth inequality and (2) make the wealthy’s influence on politics illegal (in various ways). Let’s start with wealth inequality.

Wealth and income inequalities lead to downstream inequalities in our politics. People have more money than others, so they can influence politics more than others, often through paid advertising, private donor access, lobbying/think-tank efforts, etc. To reduce this imbalance, you can enact policies to reduce economic inequality before any individual actor begins interacting with democratic institutions. However, your mileage may vary. A lot of these policies have downstream economic and social tradeoffs that many wouldn’t find strictly or net desirable. It comes down to how big of a problem you think inequality is principally and empirically. Is a progressive income tax a Pigouvian tax on the socially negative consequences of having radically higher income? In some sense, I would say yes, but a thoughtful approach is needed to avoid overly deleterious effects on the economy.

To start, establishing a sovereign wealth fund is a great way to tackle wealth inequality directly. Institutional design matters, but a dividend-paying sovereign wealth fund would horizontalize a potentially large proportion of wealth. Norway has a sovereign wealth fund, and at the time of writing this, it’s worth around $300,000 for every single Norwegian citizen. Assuming a conservative 3% withdrawal, that is about $9,000 of capital income for each Norwegian, every single year, fully funded, without any deficit implications. Norway does this with a complicated system of taxes on resource rents and state ownership. The individual intricacies of Norway aside, the U.S. has a lot of natural resources, with resource rents representing about 1% of GDP any given year. Taxing this into public institutions would be a methodical way to fund a U.S. wealth fund without much economic distortion. The U.S. could also buy a balanced portfolio of securities during downturns, transfer Federal Reserve assets to a sovereign wealth fund, or dedicate other forms of taxation/fees to funding a sovereign wealth fund. I’m open to the best, least distortionary, funding mechanisms and exact institutional design, but it is certainly possible, over a generation or more, for the U.S. to responsibly build a large sovereign wealth fund.

If the U.S. had a wealth fund the size, equivalent per-person, to Norway, it would be worth over $100 trillion. $100 trillion worth of wealth owned equally by each citizen represents a radically equal distribution of wealth compared to today. The median person was worth about $200,000 in 2022. This seems decent, but of all the wealth in the country, the bottom 50% owns around 1% total. A sovereign wealth fund would compress this distribution significantly, limiting the influence of the wealthy by segmenting the total wealth available to them. It would do so over several decades as the funds’ capital accumulates, and since we could decentralize the management of the fund and use less distortionary taxes to fund it, there’s not much reason to expect economic calamity on account of this new economic structure.

Next, to all the Georgists out there, a land-value tax (a form of wealth tax) would be another excellent way to limit wealth inequality. However, this, along with wealth taxes generally, are constitutionally dubious. So, while a land value tax is a great way to limit wealth inequality, I’m not sure if there’s much appetite to amend the constitution specifically to tax land. Though, you never know, and it’s still important to advocate for such a policy even at the federal level to keep it in the zeitgeist (at least somewhat). More on the court later.

Other than land taxation, taxing consumption progressively would be an effective means to reduce economic disparity and downstream wealth inequality. Functionally, this would mean making all investment pre-tax and ratcheting up the income tax rates on the rich significantly. For those unfamiliar with the current U.S. tax code, the U.S. makes certain spent dollars ‘pre-tax.’ 401k accounts are perhaps the most well-known example. Let’s say you make $100,000 per year and you put $20,000 into your 401k. The government taxes you as if you made $80,000. I would argue we should treat literally all investments this way.

This might seem self-defeating. Taxing capital income and investment generally leads to less investment and thus, less wealth inequality than otherwise, but it’s important to consider that the investments of the wealthy are not inherently anti-social. We want the wealthy to invest their money into productive enterprises and innovations. What we don’t want is the wealthy having an inordinately lavish amount of consumption, which might include political spending. Take Elon Musk’s personal net-worth of around $350 billion. Let’s say he sells $1 billion worth of his portfolio (0.3% of the total) and invests that money into a technology start up. Currently, he wouldn’t be able to invest the full $1 billion because he must pay taxes on any capital gains associated with that $1 billion sale, which represents some allocative inefficiency and deadweight loss on account of the capital gains tax. He pays the same tax if he uses the $1 billion to fund a presidential campaign.

Under my tax system, he pays no taxes on the $1 billion he invests in a company, but he pays an extremely high tax if he consumes $1 billion by spending it on a political campaign. What the top-marginal rate should be on consumption above a certain amount is somewhat subjective, but I would argue a person attempting to consume $1 billion in a single year should probably pay upwards of a 70% rate, and the best part of such a tax code is that it is highly allocatively efficient because it does not effect investment decisions, only consumption decisions of the wealthy. Right-Libertarians might say this has some negative downstream effects on lavish consumption industries like high-end vacations or yacht manufacturing, but this doesn’t delete the $1 billion worth of consumption. Simple math would show the wealthy person still has $300 million to buy whatever they’d like, and the other $700 million is effectively a consumption transfer socialized to the public. Meaning, while we might see the high-end vacation and yacht manufacturing industries take a hit, industries regular people involve themselves with would experience a boost in demand from this additional $700 million.

These examples are not quite exact because the tax implications of business investment are complicated and even my system would have marginal rates, but the gist of it is that the wealthy would have significantly less money for lavish consumption, and if part of that lavish consumption includes buying lobbyist time or political campaigns, they’re going to have much less money to do that given the taxes they owe.

There are many other approaches to directly/indirectly reduce wealth inequality upfront: unionization, state enterprise, other taxes, etc., but the two ways I described above are significant initial starts which don’t require a radical redesign of our institutions.

Perhaps the wealthy could argue, even under my tax system, they might be ‘investing’ in a business which engages in political consulting or campaigning, so my tax system doesn’t stop all political consumption by the wealthy. Society needs to address the types of spending allowed in politics as well. On the political spending side itself, I favor a simple approach: ban all private money in politics. The only money in our politics should be completely horizontally distributed. This could come in the form of adults having a set allocation of dollars (vouchers) they get each year to distribute to political candidates of their choice. Seattle experimented with such a policy after 2015, and the distribution of voucher dollars was much more representative of the average person than the average cash donor. Such a policy isn’t perfect as not everyone distributes their voucher, but this is more of a problem with our civic institutions than the voucher policy itself.

This might seem like an unrealistic solution, especially given the current Supreme Court’s opinion that money is speech, so what are some potentially more feasible ways to limit money in politics in America? Restricting the types of advertising available to candidates, lowering the personal contribution limit for political campaigns, and making corporate/PAC contributions illegal would be a good start. However, even with these, it likely requires a very different Supreme Court to get any one of these things through, but advocacy probably shouldn’t be limited to the narrow, right-wing, political spectrum of the Supreme Court. These are good ideas, so they should be advocated for, even if they require a constitutional amendment, a change in court composition overtime, or local/state-level advocacy.

I agree with the Supreme Court, money is effectively a form of speech. The court, however, refuses to engage in a holistic analysis of this issue. If money is a form of speech, that necessarily means the wealthy have a louder voice than everyone else, which undermines a person’s basic right to political equality. The working class of the world should not have to exhaust themselves combatting a disproportionately loud and wealthy voice. Rather, the wealthy, the poor, and the middle class should occupy the same floor of access to political influence.

well written post! i wasnt entirely convinced though.

the underlying assumption here is that different people holding different amounts of social power is a bad thing. if you eliminate wealth inequality, this problem isn't solved though. if true equality means everyone truly has an equally "loud" voice, then after solving wealth inequality, we need to solve the problem of some people... literally having louder voices.

some people are more charismatic than others. some people are more intelligent than others. some people have more wealth than others. i'm not american so i may mess up some details, but elon musk was giving away a million dollars to people that voted in Wisconsin, yet the guy he supported got dumpstered.

if any disparity in social power is de facto bad, it seems like wealth may be down the list compared to kneecapping people that are unusually charismatic? all the wealthy people are getting dicked down by tariffs, too. bill gates is much richer than donald trump, but i dont feel like his political impact has been any larger. donald trump and elon musk are just unusually charismatic people.

and i will admit it's entirely possible that a lower amount of wealth inequality is just better for a society, but i feel like this problem would be down the list. it may be nice if wealth inequality reduces as some vague long term goal, but we don't need wealth inequality reduced to pass tons of legislation that directly improves the lives of poor people right now. taxing jeff bezos a lot does effectively nothing for his employees.

i think it's politically ineffective too. people will hear "jeff bezos can spend X amount of money for X years and still have X left at the end!!!" and think "oh jeff bezos? the guy that created the company that gets me literally anything i want delivered to my doorstep in like 2 days? good for him i guess"

when people on the left say "the biggest problem we need to focus on is wealth inequality", it's like saying "im overweight and the easiest way to lose weight is to amputate a limb". let's worry about being healthy first, and the weight loss may follow.