Following from part two, today we tackle landlords. Much like the capitalist who earns money from his money rather than from his labor, the landlord does much the same, earning both rent from land and ire from the left. Not only do landlords earn money from unproductive activity (owning land), they do so at the direct exclusion of others, and the kicker is—no one can take credit for creating land.

'Land rent' (money derived from land itself ) is, by definition, unearned and/or the result of speculation. It’s important to distinguish between rent and productive activity. For example, a farmer earns money from his land by planting crops, harvesting, and selling them. However, the farmer also earns land ‘rent’ (i.e. the value of happening to own a specific plot of land, separate from its productive use).

A more intuitive example is real estate. Take a walk through a typical Zillow listing in the San Francisco area, and you’ll find $1MM+ houses for sale that are either rundown or less than 1,200 sqft. This isn’t because the reasonable cost to build such a house is over one million dollars. Rather, this is because of the land's location. Demand to live in San Francisco is so high that people are willing to pay a lot for the location, and current residents benefit from this demand, whether they actively contributed to it or just happened to be in the right place at the right time.

Royalties from landed resources or rent payments to landlords fall in the same bucket. This is income, not from services provided or entrepreneurial activities, but rather from luck, circumstance, and/or speculation. At best, land rents come from unproductive activity, and, at worst, land rents result in suboptimal economic and social outcomes. For example, someone refusing to develop land due to their desire to speculate on land value, resulting in a housing shortage.

There’s a simple solution to this problem, and it’s compatible with other leftist goals like public ownership and/or decommodification.

Land Value Tax

Replaces: The Property Tax

The land value tax (LVT) is a tax on the assessed value of land. Let’s say a local government determines a plot of land is worth $20,000, and the LVT rate is 10%. That year, the owner owes $2,000 in taxes.

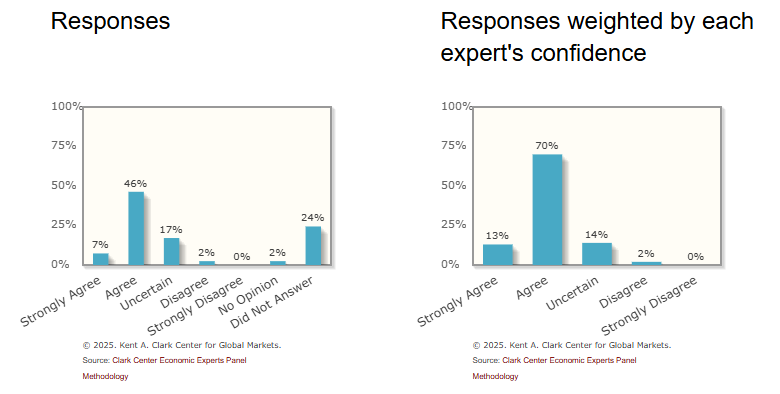

This tax is perhaps the most widely favored tax in the history of modern economic discourse. The City of Detroit proposed a land value tax a year or so ago, and economists were asked about the potential of the land value tax to “enhance the incentives for owners to develop their land and thereby give a substantial boost to local economic growth.”

Even the single person who disagreed recognized the value of taxing land. He just wasn’t sure about using the word ‘substantial’ to describe its benefits for Detroit.

So, why the land value tax? What makes it good? And why should the left include it in their policy platform?

I’ll make three main points about the LVT:

The LVT is productivity and growth enhancing.

The LVT raises a lot of money.

The LVT significantly reduces inequality.

Productivity & Growth

Most cities tax property, which taxes both land and the improvement’s value on top of the land. This causes lower levels of investment, something the left shouldn’t support.

The tax code shouldn't punish, for example, a land-owner building hundreds of affordable units on top of their land. Cities, sometimes recognizing this problem, will split a property’s valuation into its land and improvements, allowing the city to charge a different rate for each.

Doing this, cities see increased building and higher density, in line with theoretical predictions. By no longer taxing improvements, governments could increase development and housing affordability across the board, all while punishing land speculation, resulting in a more stable, pro-growth economy.

And the best part of a land value tax is that it has limited deadweight loss. There’s an old saying, “if you want less of something, tax it.” This is because most taxes, to some degree, disincentivize the taxed activity, whether it’s labor income, capital income, wealth accumulation, consumption, etc. This effect is overblown by some, but it's real, however marginal.

Unlike the things mentioned above, taxes don’t destroy land to any degree. This is a key reason why economists rank the land value tax so high relative to other forms of taxation. Society gets a pro-social tax policy in exchange for very little or no deadweight loss, and that’s before we do anything with the revenue.

Revenue

Speaking of revenue—the LVT can raise a lot of it. Every locality, and countries at large, have land. The United States has a lot of it. Lars Doucet, Georgist extraordinaire, provides perhaps the most robust survey of the literature and analysis on how much an LVT could raise. He goes through various valuation methodologies, concluding that a guy named Smith’s estimates are most reasonable (read here for more), then applies two different LVT rates, 5% and 8%, and sees how much revenue they could raise in 2019.

Lars charts this compared to other large buckets of federal spending, along with a more conservative valuation methodology from the Fed as a lower bound. Charting these revenues as a percent of 2019’s nominal GDP, we see the following:

We can take these percentages and apply them to 2024’s GDP (I take $29 trillion to be conservative) to get a basic, though not robust, idea of the potential revenue an LVT could raise today:

The federal budget deficit in 2024 was ~$1.8 trillion. This means, on the lower bound, an LVT could almost eliminate the budget deficit. At most, it could eliminate the budget deficit and provide tax revenue worth $8,000 per American on top ($4.52t - $1.8t / 340MM). An expansion of social spending to this degree has the potential to greatly reduce poverty and inequality, all while boosting economic growth and productivity without resulting in deadweight loss or negative distortions.

Inequality

The land value tax is a type of wealth tax. It is, after all, a tax on the value of a particular type of wealth—in this case, land. The best justification for a wealth tax is its potential to reduce wealth inequality, but a general wealth tax comes with a lot of complications and potential downsides, like reduced investment.

The land value tax increases investment and targets a large portion of wealth directly. It’s difficult to find the distribution of land ownership, but real estate (as a proxy), tracked by the Fed, is very unequally distributed.

The top 1% own more real estate than the bottom 50%. This shouldn’t come as a surprise since all categories of wealth are unequally distributed. Land is no different.

There is also evidence to suggest that housing ownership represents a significant share of capital income, so the land value tax, by socializing land rents, captures progressive revenue for the state and, in part, solves a major driver of inequality—housing affordability—by incentivizing additional building.

On balance, a general wealth tax might remain a good idea, but the lowest-hanging wealth tax available is the land value tax. About 18% of the assets owned by the top 10% is real estate, and, in addition to the land value tax, there are better ways to tackle wealth inequality than a general wealth tax (which I will discuss in later articles).

Closing Thoughts

I’m far from the first person to speak about the importance of a land value tax. The land value tax could go on any platform from left to right since it's not incompatible with a leftist disposition on housing and land. A leftist could support a great expansion of public housing and public ownership of resources while still supporting a land value tax on any remaining private ownership.

The land value tax has its hurdles. The constitution arguably does not allow a land value tax at the federal level, and all advocates have the burden of explaining how land valuation could work. Luckily, the land value tax is often legal at the local and state level, where governments already have systems to value properties, so the advocacy chain seems clear: (1) say the community should value improvements and land separately, and (2) lower the rate on improvements while raising the rate on land until the improvement rate goes to 0%.

The LVT, in effect, is a fee to hold land, making pure land speculation and unproductive activity costly. No longer can someone sit on a valuable piece of land for free, incentivizing them to use the land for some productive purpose, like housing or industrial development.

Those on the left have several reasons to advocate for a land value tax all else equal: (1) It increases growth while reducing speculation, (2) it raises a lot of revenue mostly from the wealthy, and (3) it reduces inequality. It's one of the very few win-win-win economic policies, and the left should back it with full force.

"Most cities tax property, which taxes both land and the improvement’s value on top of the land. This causes lower levels of investment, something the left shouldn’t support."

I don't think this is a useful statement. Any tax that lowers demand will lower investment: but this does not make the tax bad. It just means there are tradeoffs.

Henry George advocated LVT as the "Single Tax", the only tax, no income or sales taxes. Do you agree?