At this moment in my life, the left provides me with a stable home. I’m drawn to the equality of people, distributional justice, community, solidarity, etc. As a policy guy, I’m also interested in the ways in which policies can better reflect my worldview, or how policies might prove my worldview impractical. Bernie Sanders, AOC, and Elizabeth Warren are great examples of left-leaning politicians I can support with enthusiasm.

However, they, along with almost all members of the progressive/socialist left, have a lot of work to do regarding taxes. Often, it seems, members of the left resort to simplistic, punitive tax policy. In leftist circles, you hear a lot of “We should tax the rich! We should tax corporations! They need to pay their fair share!” I’m not antagonistic to this way of thinking in principle. There are intrinsic reasons to believe taxing the rich is good in and of itself. Wealth accumulation and high income inequality cause a lot of societal issues, but the left tends to rely on current tax structures and upping those rates. Sometimes you’ll hear about wealth taxation or taxing unrealized capital gains, but more often it's taking things like the income tax, capital gains tax, and corporate tax, looking at the upper-income rates, and increasing them.

Some issues with this approach—

These tax policies don’t raise enough revenue to finance the types of things that the left desires.

There are inefficiencies with these forms of taxation.

They aren’t the lowest hanging fruit; and

They aren’t the most progressive.

There are better ways to raise revenue, and the left should adopt them. Skepticism of the wealthy, wealth concentration, income inequality, and the capitalist class go hand in hand with the forms of taxation I’ll describe. It’s important to divorce the idea of taxing corporations or the rich using our current tax tools because it can make the left look foolish and naïve at best, and at worst, it leaves the left with a worse policy platform.

Expenditure Tax

Replaces: Capital Gains Tax & the Income Tax

The left loves the capital gains tax, and it makes sense. Earning money from owning capital? Cringe! Mr. Capitalist with his stacks of cash from sitting around selling stock didn’t actually do anything to earn all that money, so when the rich sell their stock, we should tax it at a high rate.

An objection—the big ‘problem’ with the rich isn’t the investments themselves. People don’t tend to intuit injustice from the size of a wealthy person’s savings accounts or their portfolio’s market value. People do see a problem when the wealthy buy multiple mansions, yachts, news organizations, elections, etc. It’s the consumption of the wealthy that causes social exclusion and an air of elitism. Of course, the types of investments the wealthy make can harm society (see my first Substack), but if it's the type of investment that is the issue (i.e. buying elections or news media), a generalized tax on all investment allocation isn’t the best solution. We should just limit, ban, or regulate those specific types of investments.

Otherwise, the process of investing capital provides utility for the rest of us, and the capital gains tax distorts that process in important ways. Take a person who owns shares in a business valued at $1 million. Say he sells these shares in order to start another business. This is entrepreneurial activity that creates jobs, raises output, and creates new innovations, but the capital gains tax forces this person to pay a chunk of that $1 million to the government, resulting in either less startup capital for his new business or a delay in opening, both of which are not optimal societal outcomes.

The capital gains tax also causes ‘locked in’ effects, where tax planners refuse to make optimal selling decisions just to avoid the capital gains tax, another economically suboptimal decision (see here for more on capital gains taxes).

One could argue that these negative allocation effects are worth the social benefits of lower inequality and the public use of the tax revenue, but the capital gains tax only raises an amount equal to ~1% of GDP, or a couple of hundred billion dollars annually. It’s not difficult to make this up with other sources of revenue.

The income tax also affects investment because it doesn’t distinguish between income invested and income consumed. In reality, there are exemptions for certain kinds of investments (like 401(k) contributions), but in practice, the income tax also reduces the pool of available funds for investment. Luckily, we can raise significant revenue and reduce inequality without distorting investment decisions.

Introducing the ‘expenditure tax.’ The game changer here is that the tax still taxes your income from capital and labor, but it allows for deductions for all investments made. For instance, if a person makes $75,000 in a given year, and they invest $10,000 in an investment account, they pay tax as if they only made $65,000. They ‘deduct’ the $10,000 from their income. This is because they did not consume the $10,000 this year. Let’s say the following year their savings account appreciated by 20% to $12,000. The same year, they made $80,000 from wages. During the year, they sold all $12,000 in their investment account to purchase a used car. They pay tax as if they made $92,000 since they consumed both their income and investments.

Since the wealthy consume much more, this tax system would result in a transfer of consumption from the rich to the poor, as the rich now pay tax on their lavish consumption, and the poor have more services or social insurance programs from the state. The fringe benefit of advocating for such a tax code is that it’s very difficult to argue against. It puts right-wingers in the awkward position of defending the lavish consumption of the wealthy. No longer can they say, "Well, Mr. Socialism, that 70% tax rate sure sounds nice until investment dries up!” All investment is tax-deductible now, so the wealthy are free to invest as much as they want, but if they want to pull out $100 million for a new yacht, Uncle Sam needs his fair share come tax season.

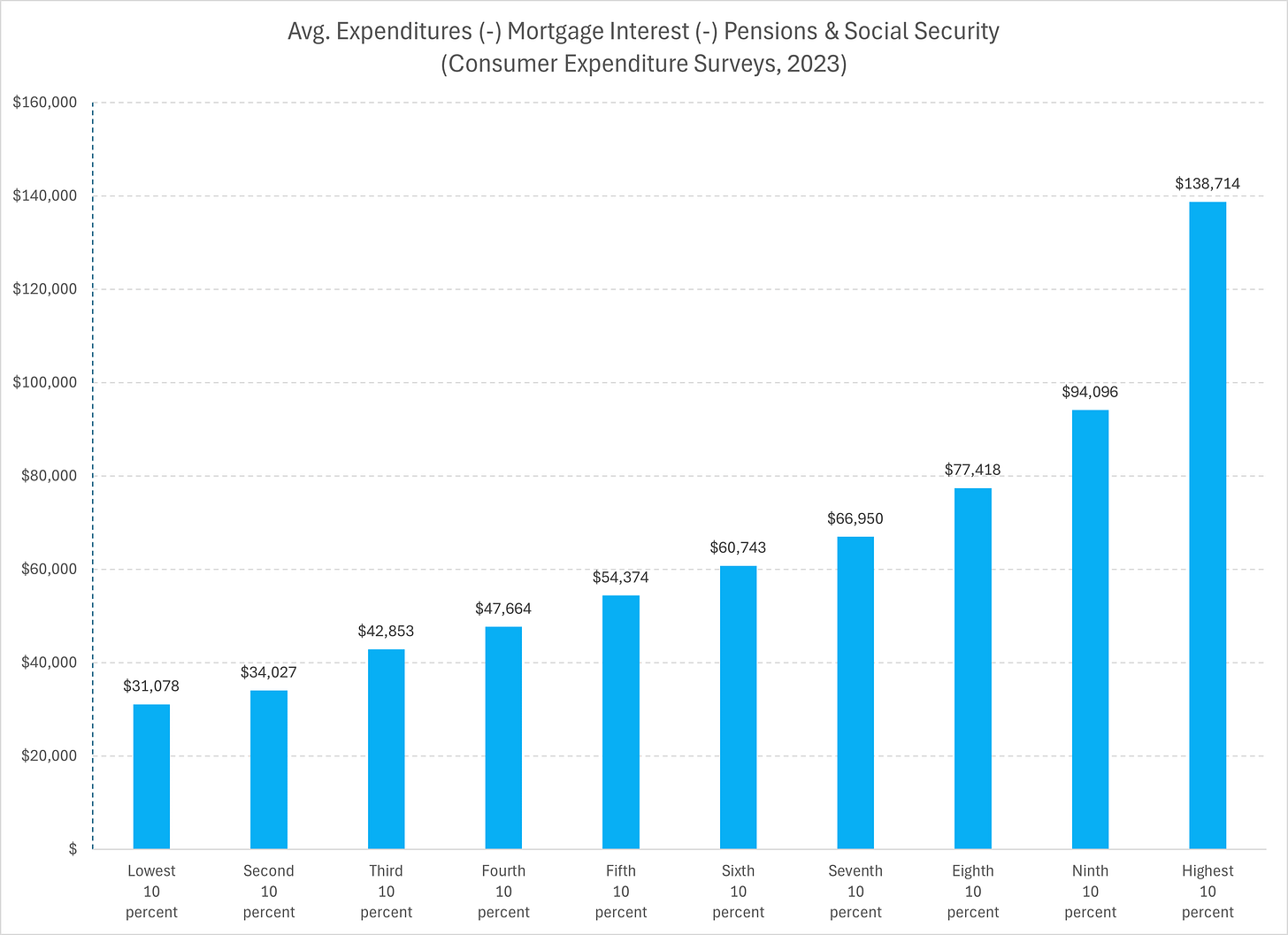

There aren’t great papers estimating the revenue of an expenditure tax since it would require in-depth information on all savings and investment decisions, but expenditure tax rates could be such that they are revenue neutral to the current income tax, or even higher, depending on how high society wants to set the rate. This isn’t a robust way to estimate revenue since the effects of taxation are dynamic and complex, but for a basic exercise, let’s start with a look at the consumer expenditure survey broken down by deciles in 2023. We can see how uneven American consumption is.

Per the tax base of the expenditure tax, the top 10% of people, on average, consume around 4.5 times what the bottom 10% consume. Only the fifth percentile and above have an average pre-tax income that eclipses their average consumption. This is because the bottom half of people disproportionately rely on sources of income like benefits, debt, savings (if applicable), family/community transfers, etc.

If we take these deciles of consumption and multiply them by the number of consumer units (which, on average, have 2.5 people), and then apply a tax to each decile’s consumption base, we get the following outcomes:

The tax applied is 10% at the first decile, and it increases by 20% (i.e. 10% * (1 + 20%)) for each subsequent decile. The total amount of money raised would be ~$2.8 trillion, which is about $700 billion more than the U.S. raised from all income taxes in 2023. Calculating tax collection is not as simple since there are concerns about tax avoidance and downstream effects with any tax system, but tax elasticities likely wouldn’t be so high that the U.S. couldn’t create a similar bracket structure that raised similar or greater levels of revenue from the consumption base.

This tax bracket might look suspect to some. The poorest are still expected to pay 10% of their consumption, and the richest pay a majority of their consumption in taxes, but the revenue raised doesn’t go into a furnace. The state uses this revenue for pro-social programs like Medicaid, child allowances, public education, etc., all of which disproportionately benefit the lowest-income/lowest-consumption households.

Let’s assume this revenue is flatly distributed. Every household receives the same distribution. In practice, this distribution would likely be progressive itself, but to illustrate the point:

Reading the chart left to right, we see the number of consumer units (essentially households), their pre-tax expenditure, taxes collected, their post-tax expenditure, the sum of all taxes flatly redistributed, and their final post-transfer expenditure. The bottom 50% of people are all net better off, and the top 50% of people are net payers into the system. This mimics the tax collection of the current U.S. income tax system, where the bottom 50% pay very little, if any, tax, and the top 50% pay more tax as they go up in income.

To put this in perspective, under this expenditure tax system, we see the following pre- and post-tax distributions of consumption:

Before this tax system, the top 10% consumed about 4.5 times more than the bottom 10% on average. Since the rich consume so much more, even before the distribution of tax revenue, consumption inequality drops by almost 50%. After a flat distribution of tax revenue, consumption inequality is more than cut in half, ending up at 1.8 times.

This method of taxation raises significant revenue, ensures a radically progressive distribution of consumption, all without hurting investment. It allows progressive politicians to campaign on an efficiency agenda while also messaging toward the salient inequality that people see around them.

Closing Thoughts

This article ended up being longer than I expected, so I will make this a series going forward. The left should take a page from the tax wonks of the world and rethink taxes from the ground up. Collective ownership, solidarity, and community are not sacrificed in a world with a wonky tax code. They are further enabled, and I hope the left can take the tax wonk mantle from the center and right-wing.

my goat

Production (investment) and consumption are two sides of the same coin. No one will produce anything if there are no customers, and you can’t consume something if it hasn’t been produced. Taxing either activity will have a similar Debbie Downer effect on the economy.

There is another option. Tax something that represents the true definition of unearned, unproductive wealth – land values. Replace income and sales taxes with the Land Value Tax.

A personal example (confession!) to illustrate: The house (or, more accurately, the land under the house) that my wife and I purchased decades ago has insanely appreciated. Good for us! But who else has benefited? A similar gain in the stock market would, at least in theory, have been our reward for providing investment capital to grow businesses, create jobs, etc. But land value is a zero-sum game. Our gain comes at the expense of others who can’t afford a place to live.

The advantages of the Land Value Tax:

-Simple to define and enforce. The tax would be “x” percent of assessed land value, no exceptions. You can try to hide income but you can’t hide land.

-Progressive and pro-growth. The wealthy owners of high-priced land and would pay a disproportionate share of the taxes, but the marginal tax on both income (production) and consumption would be ZERO – a win-win for both liberals and conservatives.